In A Pig's Ear

by Dorty Nowak

There are 72 recipes for animal body parts I have never eaten in Le Meilleur Cuisine de France. I purchased the cookbook, a staple in French kitchens, when I first moved to Paris, and over the past five years it has become a trusted guide for my culinary adventures. However, the section titled “Les Cochonailles et Les Abats” (Pork Products and Offal) remains untried territory.

It’s not that I’m a vegetarian. In fact, I’m a regular customer at my neighborhood butcher shop, La Boucherie Daguerre. The front half of a cow, with black paint chipping off its metal hide, hangs above the door and inside a small army of butchers in stained white smocks moves swiftly across the sawdust floor filling customers’ orders. Even though the cuts of meat are different, I have no trouble finding the beef, and I’m particularly fond of the marvelous roast chickens. Here too is a vast array of food I’ve never tried. Each visit, my glance would skim with practiced ease over the motley-feathered chickens, heads and feet attached, the trays of rognon (kidneys) cervelle (brains) and tripe (intestines), to settle on something safe. Indeed, I felt confident about my ability to navigate the perils of the butcher shop until the day I went to buy a roast for dinner and found myself eye to eye with a dead boar, grinning at me through his enormous tusks. He was draped over the counter above the roasts. I fled, and we had pasta for dinner.

Avoiding abats is easy enough when cooking at home, but much more difficult when dining out. The French have a fondness for them, and it is rare not to find at least one dish on a menu. As I am averse to spending a small fortune for a meal and then not being able to eat it, I purchased a pocket menu master, a handy French-English dictionary including most common menu items. Unfortunately, the menu master didn’t save me from the andouillette. Andouillette, a prized delicacy, is a sausage made from, pigs’ intestines, and it smells just like you would imagine pigs’ intestines to smell. I know because one time I ordered it by mistake, thinking it was andouille, the delicious, spicy Spanish sausage. Fortunately, the fries were good.

Dinner invitations present another set of problems. While most of my French friends kindly defer to my “picky American appetite,” I am not always so fortunate.

Refusing to eat what my hosts have prepared is not an option, and neither is the menu master. The only recourse is to shepherd any offending morsels around the plate and try to hide them under something else, a trick I learned as a child.

Even this subterfuge failed me when I encountered Aunt Adrienne’s tête de veau.

Adrienne had decided to prepare a special meal for me, her niece’s American friend. She had obviously gone to a great deal of effort. The table was set with crystal, china, and the usual challenging array of silverware. Delicious smells wafted from the kitchen, promising a wonderful meal. Even so, I was anxious. “What’s for dinner?” I whispered to my friend. “Veal’s head, it’s a specialty,” she whispered back. Wishing I hadn’t asked, I stared apprehensively at the lovely Limoges china dish Adrienne set on the table. As she lifted the cover with a flourish, I fully expected to see a calf staring at me with mournful eyes. Fortunately, tête de veau looks like greasy pot roast. As Adrienne was watching me, I had to eat some. I downed several morsels of meat, but I can’t say what the gelatinous grey stuff that surrounded the meat tastes like.

I might have continued indefinitely avoiding a significant portion of French cuisine

had it not been for my downstairs neighbor, Nicole. I spent hours in the kitchen with Nicole, watching her prepare dishes, never with a recipe. Notebook and pencil in hand, I’d ask how much of this or that ingredient to use. Her answer was always the same, “I don’t know. This is how my Mother did it.” Under Nicole’s tutelage I learned how to make a soufflé that didn’t look like a pancake, and to always serve a plain green salad with the cheese course.

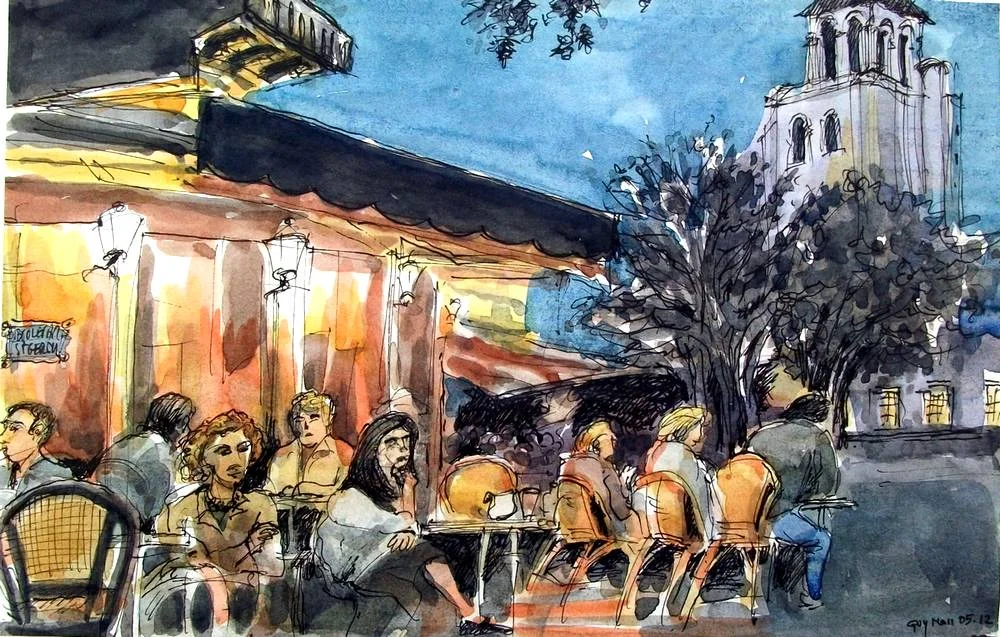

Nicole taught me how to cook the French way, but one day she taught me a far more valuable lesson. We had gone to lunch in a small neighborhood café, and Nicole was delighted to see oreilles de cochon (pig’s ears) on the menu. “A real delicacy,” she exclaimed. I ordered quiche. The oreilles de cochon were small, black and hairy. They were disgusting. “Try one,” Nicole urged. “No thanks,” I said, hastily taking a bite of quiche. Nicole looked at me for a moment, then began to speak in her quiet way. “I remember one winter during the war when we did not have enough to eat.” Surprised, I looked up from a forkful of quiche. I knew Nicole and her family, like so many people in Europe, had suffered greatly during WW II, but she never spoke about the hardships of that time. She continued, “My father was able to find work with a farmer and he traded his labor for a pig. We were so happy. My mother made wonderful meals out of that pig, and we ate every bit of it.”

I sat, staring at my plate, digesting Nicole’s words. “I think I’d like to try one of those oreilles de cochon.” I did, and it was delicious.

Dorty Nowak is a writer and artist living in Paris, France, and Berkeley, California, who writes frequently about the challenges and delights of multi-cultural living. A former educator and insurance executive, she helped found the Oakland School for the Arts. She is currently developing a collaborative project, ”Where Do I Belong,” involving artists and poets from Europe, Australia and the U.S.